Improving Character-based Decoding Using Target-Side Morphological Information for Neural Machine Translation

(Passban et al., 2018) at NAACL

Translating in “morphologically rich languages” (those with a lot of verb conjugations and noun declensions) is difficult. These authors seek to circumvent the issues by including morphological tables as inputs to their decoder.

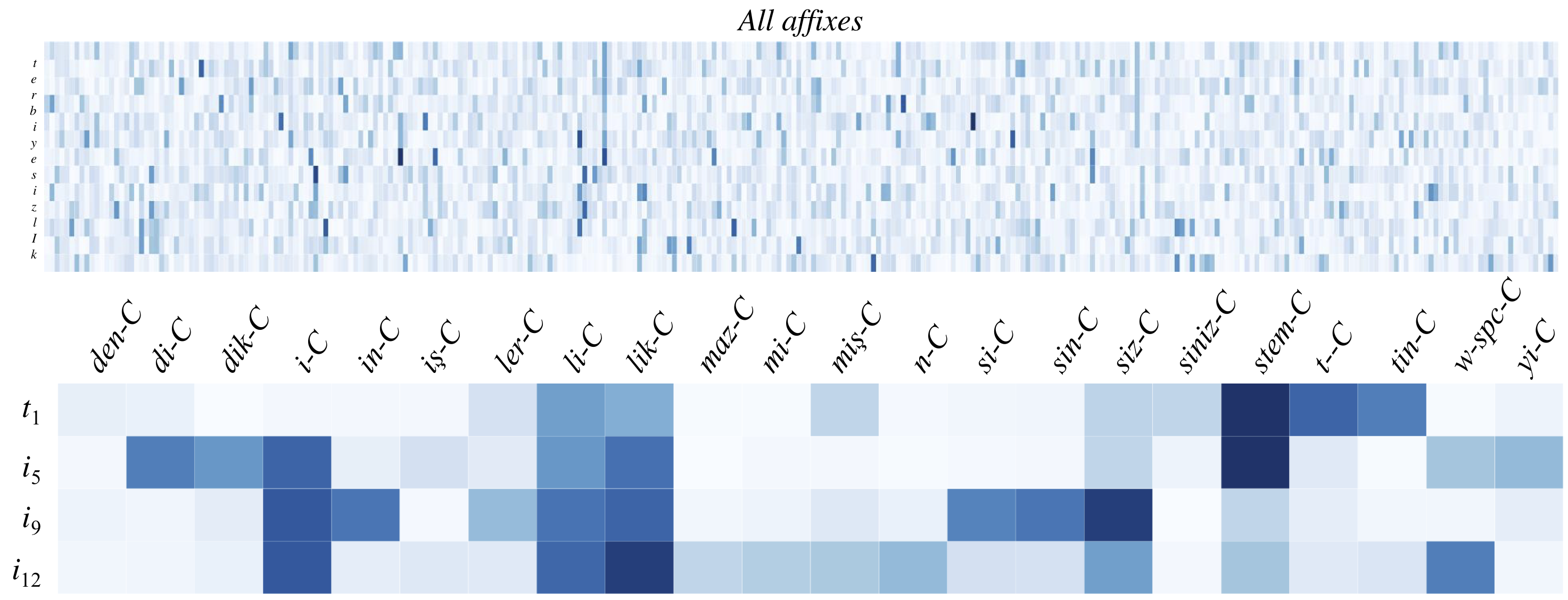

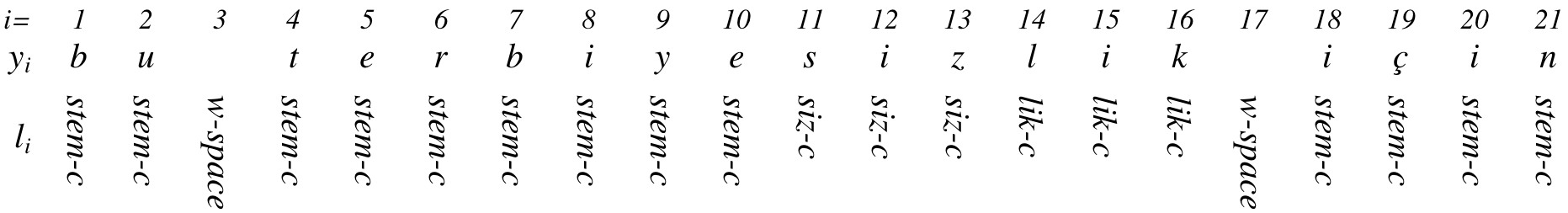

(Attention over a morphological lookup table throughout the Turkish word terbiyesizlik, which can be decomposed as terbiye-siz-lik.)

The authors’ model for translation is a character-level neural system, which decodes by producing one character at a time. The authors argue that the decoder doesn’t have enough information to track many of the constraints on which sub-word structures can appear together. Plus, the long sequence of characters (average 75–100 in English) makes it hard to remember information from earlier in the sentence.

The space of possible characters is smaller than the space of possible words, but the constraints on which character to emit next are less straightforward. To better guide this selection process, the authors propose three adjustments to the neural decoder:

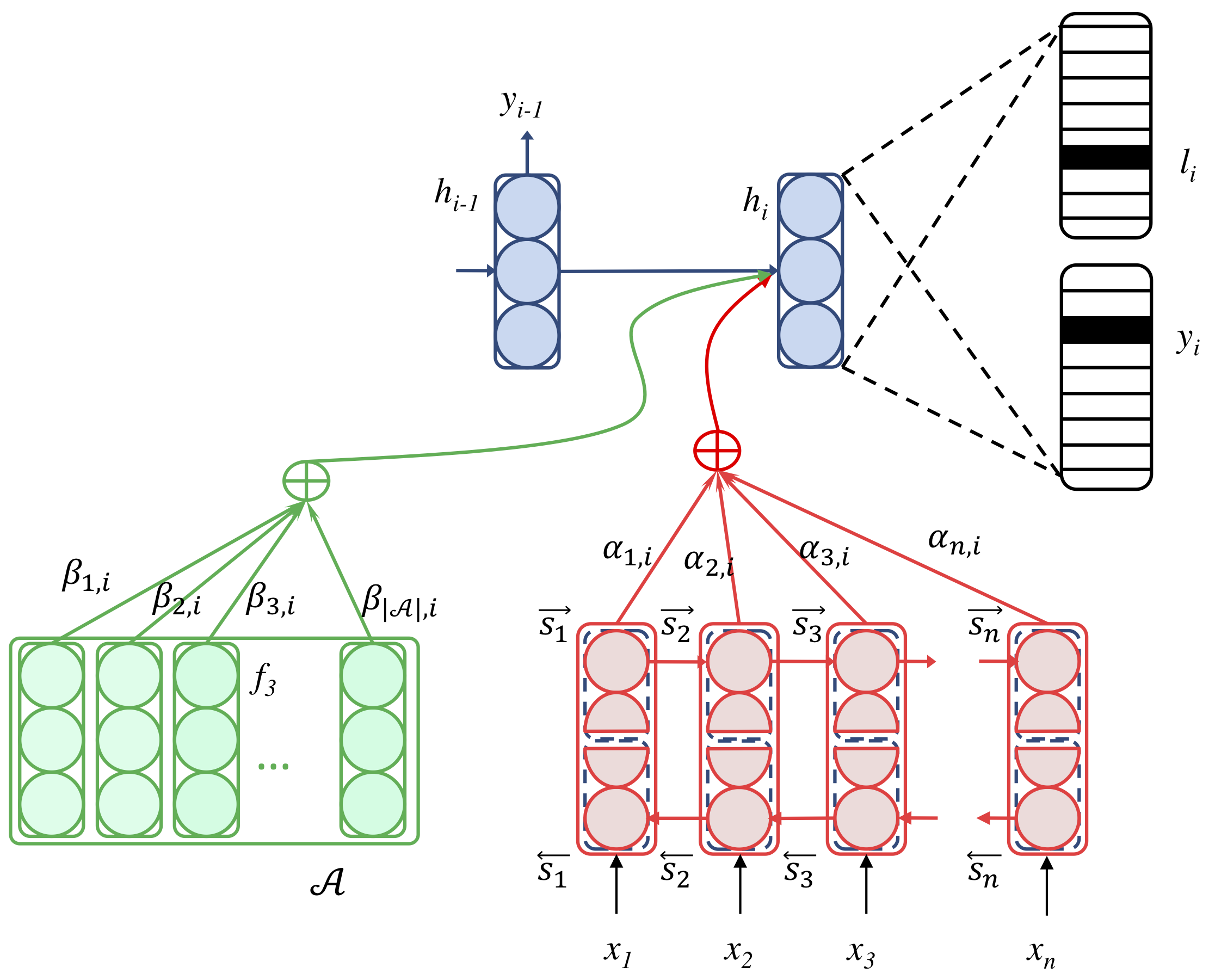

- Augment the decoder with a table of target-side affixes. Attention is used to search the table for character sequences relevant to the character that the decoder just sampled.

- Let the decoder predict both a character and a morphological annotation of the character.

- Combine these two.

The authors claim that the model is general enough to accept any arbitrary type of feature into the decoder.

The authors use Bahdanau attention in a normal sequence-to-sequence model, which takes in byte-pair-encoded (BPE) source sentences and produces character sequences In the target language.

They then augment this in the ways listed above. First, they create a table of morphological affixes. Then they use attention—a softmax over learned weights—on these entries to select the most relevant affixes, and this is fed into the decoder.

The second refinement is to additionally predict which morphological affix \(l_i\) we’re currently looking at. This gives us an updated objective function:

\[\lambda \sum_{j=1}^N \log \Pr(\mathbf{y}_j \mid \mathbf{x}_j; \theta) + (1-\lambda) \sum_{j=1}^N \log \Pr(\mathbf{m}_j \mid \mathbf{x}_j; \theta)\]

(There’s some notational weirdness here: the \(j^\textrm{th}\) ) sentence’s sequence of affixes \(\mathbf{m}_j\) is composed of individual elements called \(l\): \(\mathbf{m}_j = [l_1, l_2, \ldots{}, l_T]\).)

Their morphological affixes, which become both the output space of the multi-task model and the contents of the morphological table, emerge from processing the target data with Morfessor, an unsupervised morphological segmentation tool. (It’s not a guarantee that the segmentation is into morphs, so the choice to call this morphology is tenuous. It’s just another scheme for tracking common character sequences, like BPE.) The affixes are then embedded into a vector space using a neural language model which maintains compositionality.

Still, their affixes are embeddings, so there’s no explicit knowledge of which affixes could encompass which characters. Nothing in their objective function attempts to correct this either. Still, impressively, their attention model attends to the right parts of the word terbiyesizlik (as shown way up above), and the vertical runs of weight are a good sign. Or is this example just cherry-picked? (This isn’t an accusation; it’s the eternal question when one example is used in a paper, but one example is often more illustrative than aggregate statistics.)

Unfortunately, the performance improvement is pretty middling—less than one BLEU point. The authors felt the need to illustrate the improvement with both a table and a figure that convey the same information. It seems that their performance comes from greater model capacity due to more parameters, because nothing about morphology is really forced to be learned.

| Model | En→De | En→Ru | En→Tr |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 21.33 | 26.00 | - |

| Reimplementation | 21.01 | 26.23 | 18.01 |

| + table | 21.27 | 26.78 | 18.44 |

| + multitask | 21.39 | 26.39 | 18.59 |

| + table + multitask | 21.48 | 26.84 | 18.70 |

Bold results were statistically significant according to paired bootstrap re-sampling, but that’s prone to Type I errors. Plus, “If you need to report statistical significance, your results are generally not that significant”—Philipp Koehn, ironically since he developed paired bootstrap resampling for MT.

Future work idea: If their model can indeed incorporate knowledge besides morphological affixes, could we use part-of-speech information to guide translation? Or what about using this for derivational affixes? And what about comparing this work to a version of the baseline with more parameters?

The bottom line: Adding a lookup table that’s searched with attention is a cool idea; it just needs to be trained well so you’re not just adding more parameters.