Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate

(Bahdanau et al., 2014) orally at ICLR 2015

I’m starting a new thing where I write about a paper every day, inspired by The Morning Paper. Let me know what you think.

This paper was the first to show that an end-to-end neural system for machine translation (MT) could compete with the status quo. When neural models started devouring MT, the dominant model was encoder–decoder. This reduces a sentence to a fixed-size vector (basically smart hashing), then rehydrates that vector using the decoder into a target-language sentence. The main contribution of this paper, an “attention mechanism”, lets the system focus on little portions of the source sentence as needed, bringing alignment to the neural world. Information can be distributed, rather than squeezed into monolithic chunks.

In general, the approach to MT looks for the sentence $\mathbf{e}$ that maximizes $p(\mathbf{e} \mid \mathbf{f})$. (Think of E and F representing English and French; the goal is to translate into English.) Popular neural approaches from Cho et al. and Sutskever et al. used recurrent neural networks for their encoder and decoder. The RNN combines the current word with information it has learnt about past words to produce a vector for each input token. Sutskever et al. (2014) took the last of these outputs as their fixed-size representation, the context. The danger here is that information from early in the sentence can be heavily diluted.

The decoder is less interesting conceptually. It defines the probability of a word in terms of the context and all prior generated words. The decoder’s job is to find a sentence that maximizes the probability of an entire sentence.

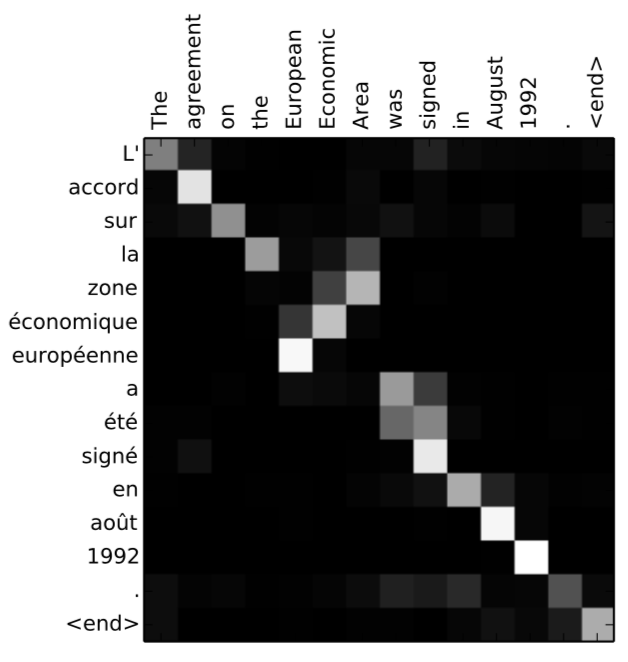

The encoder–decoder framework’s fixed-size representations make long sentences challenging. Bahdanau et al. reintroduce the “alignment” idea from non-neural MT—a mapping between positions in the source and target sentences. It shows, e.g., which words in the blue house give rise to the word maison in le maison bleu. In simpler words, which parts translated into which parts?

The attention mechanism is an alteration of both the decoder and the encoder.

This time, the encoder change is less exciting: they use a bidirectional RNN now, which is two RNNs where one starts from the end of the sentence. Its outputs now contain information from before and after the word in question.

The decoder is now no longer conditioned on just the single, sentence-level context. A weighted sum of the encoder outputs is used instead. The weights are a softmax of the alignment scores between the given decoder position and the encoder output vectors. The scores come out of a simple neural network.

Note that unlike in traditional machine translation, the alignment is not considered to be a latent variable. Instead, the alignment model directly computes a soft alignment, which allows the gradient of the cost function to be backpropagated through. This gradient can be used to train the alignment model as well as the whole translation model jointly.

With this new approach the information can be spread throughout the sequence of annotations, which can be selectively retrieved by the decoder accordingly.

Another benefit of their approach is that it’s a soft alignment, rather than a hard one. Not only does this make it differentiable (and learnable by a NN), but also it helps for agreement.

Consider the source phrase [the man] which was translated into [l’ homme]. Any hard alignment will map [the] to [l’] and [man] to [homme]. This is not helpful for translation, as one must consider the word following [the] to determine whether it should be translated into [le], [la], [les] or [l’]. Our soft-alignment solves this issue naturally by letting the model look at both [the] and [man], and in this example, we see that the model was able to correctly translate [the] into [l’].

Quantitatively, their attention model outperforms the normal encoder-decoder framework. I’m doubtful of one claim, though—that the encoder-decoder model choked on long sentences. Scores kept going up, by about the same percentage as the attention model did. They’re just lower to begin with.

The Bahdanau et al. model also nears the performance of a big-deal phrase-based model that supplemented the training data with a monolingual corpus. This is big for showing the viability of end-to-end neural MT.