Learning Global Features for Coreference Resolution

(Wiseman, Rush, and Shieber, 2016) at NAACL

Wiseman et al. previously used a neural net to rerank a coreference resolution system, and now they’re augmenting that by having a recurrent neural network (RNN) learn representations of co-referent clusters straight from the text—they’ve made it end-to-end. Their claim is that cluster-level features are a challenge to concoct, so why not let a machine handle it? And in doing so, they improve on the state of the art.

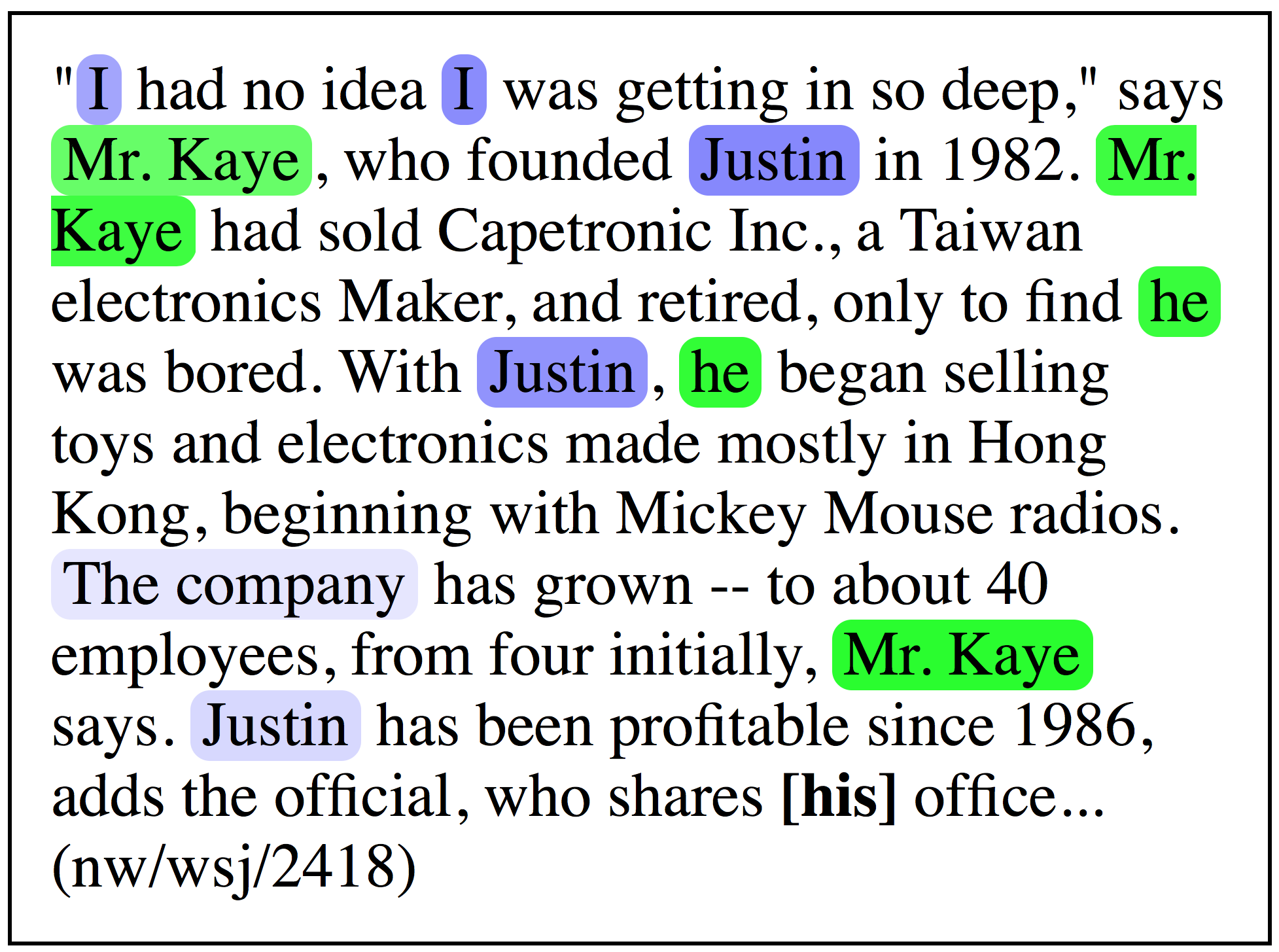

First, a primer on coreference resolution—the idea blew my mind when Sam Wiseman first explained it to me in 2015. It’s fundamentally a graph reconstruction task. You have a set of mentions—’syntactic units that can refer or be referred to’, i.e., nouns. The mentions are the nodes of our graph. These need to be partitioned into clusters which refer to the same entity. Two entities are considered co-referent if there is a path between them in the graph—if they’re in the same component. Above, co-referent mentions are colored the same—though the predictions are wrong! “I” and “Mr. Kaye” should be the same color.

To simplify the problem, we exploit the fact that the document is linearly ordered. We try to predict the antecedent of a mention. The \(n^\textrm{th}\) mention has \(n - 1\) mentions before it, or it could refer to nothing, so for each mention, we predict a value in \({1, \ldots, n-1, \epsilon }\). This is called the “mention-ranking” strategy. Each of these predictions is an edge in the graph, forming components which are our co-referent clusters.

Mention-ranking systems rely on a local scoring function defined on any mention–antecedent pair, which means inference is fast at the expense of expressivity. Still, we want a global scoring function—one that has access to the decisions made so far, because there are trends that Wiseman et al. explain: pleonastic ‘it’ and ‘you’ tend to co-occur. On top of this, cluster-level features are hard to write. The Björkelund and Kuhn feature set is extremely sparse (and a pain to wade through!).

So now the proposal is to represent a cluster as the hidden state of an RNN—particularly an RNN—run on the text of the cluster. Rather than use word embeddings, they represent each mention as a sparse vector of binary features:

\[\phi_a(x) : \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \{0, 1\}^F\textrm{.}\]This is then run through an affine map and a nonlinearity to create a dense representation. (The first vector for a mention is just the zero vector.) The RNN then reads the sequence of one dense vector per mention in a cluster. The RNNs all share parameters, but not hidden states.

Their model attempts to perform the following inference:

\[y^* = \arg\max_{y_1,\ldots,y_N} \sum_{n=1}^N f(x_n, y_n) + g(x_n, y_n, \mathbf{z}_{1:n-1})\]The local feature score \(f\) is a simple affine map relying on unary and pairwise features (or only unary features if \(y=\epsilon\). Those feature representations, though, are 1-layer linear→tanh maps of the sparse vectors \(\phi_a\) (unary features) and \(\phi_p\) (pairwise features).

Their scoring function \(g\) is more interesting. If the current mention’s dense vector is more similar to the cluster’s state, it gets a higher score—they use the dot product to compute similarity. Alternatively, if the prediction is no antecedent (\(y=\epsilon\)), a nonlinear score function is used. (Nonlinearities everywhere, I know.) It examines the current states of all clusters. To keep the weight matrix from being variable-size, they condense those cluster states to a fixed size by taking their sum.

At training time, they have gold (that is, true) clusters but not gold antecedents—remember, the antecedent idea is a computational simplification. The corresponding objective function is:

\[\sum_{n=1}^N \max_{y \in \mathcal{Y}(x_n)} \Delta(x_n, y) (1 + f(x_n, y) + g(x_n, y, \mathbf{z}^{(o)}) - f(x_n, y_n^\ell) - g(x_n, y_n^\ell, \mathbf{z}^{(o)}))\]The latent antecedent \(y_n^\ell\) is the one which maximizes the combined score function \(f+g\) above. The delta function penalizes different types of errors: false link (that is, the mention shouldn’t have an antecedent), false new cluster, and wrong link. From this, they can perform a greedy search in quadratic time, rather than an exact search in exponential time.

The authors’ system is state-of-the-art, and they note an interesting similarity to Dyer et al.’s stack pointer paper. Both use LSTMs to track the state of an evolving system, rather than directly running it over text.

The bottom line: Using RNNs everywhere makes compact, latent representations of growing sequences. They use these RNNs’ hidden states to condense global features. The authors used this to make an end-to-end coreference system that learns greedily and efficiently, outperforming the state of the art.