‘Lighter’ Can Still Be Dark: Modeling Comparative Color Descriptions

(Winn and Muresan, 2018) at ACL

Sometimes one word on a matter isn’t enough. To describe color, we resort to compositional names: “light blue”, “cherry red”. This paper looks at a group of these: comparative names. Those are names like “duller olive” or “slightly paler”.

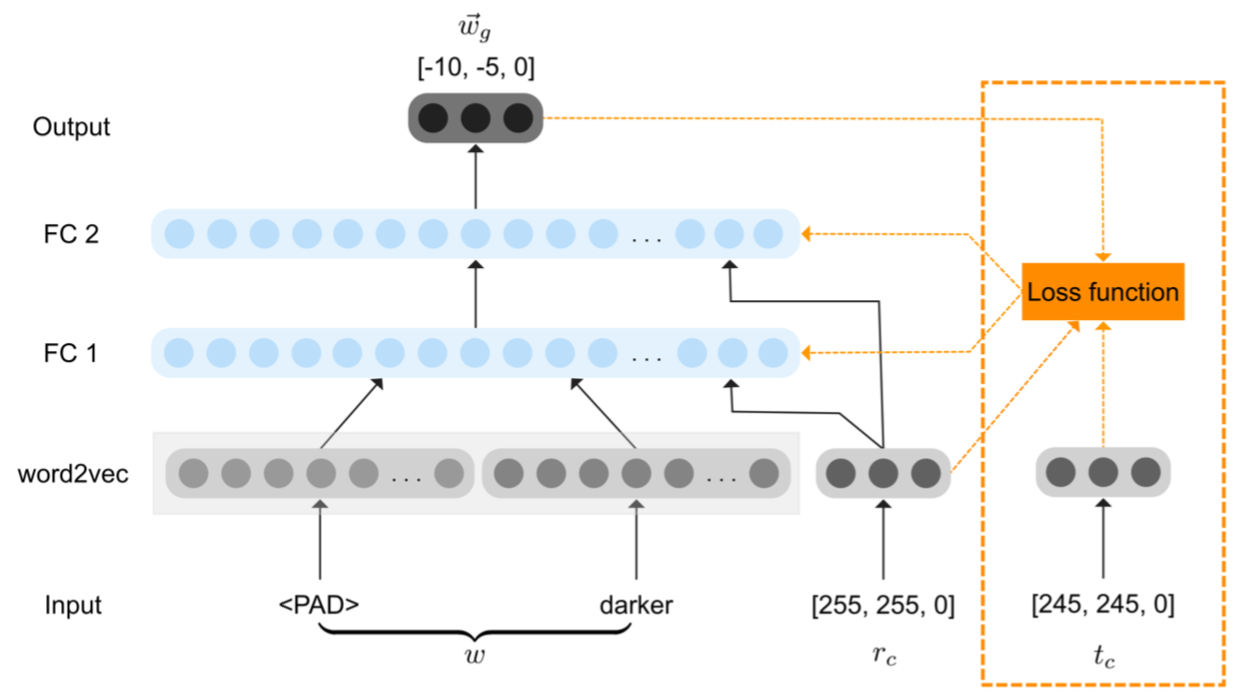

When naming a target color that is similar to a distractor, we use comparative adjectives (Monroe et al., 2017). This relates to the notion of codability, or entropy: it takes more bits to distinguish between the two colors, because our broad-level categories don’t manage to distinguish them. The work of Winn and Muresan seeks to ground these comparisons. They want to match each descriptor up to a vector, transforming “blue” + “lighter (given that the color is blue)” = “lighter blue”.

The authors used the data of the xkcd color survey, which elicited 954 color names from 500 namings and 222,500 user sessions. Many of these were compositional (though not comparative), and each label had on average 600 datapoints. (Sure, but what’s the distribution? No doubt ‘red’ was way more common than ‘filemot’.) Winn and Muresan distilled the data down to 415 tuples like (ʙʟᴜᴇ, ‘lighter’, ʟɪɢʜᴛ ʙʟᴜᴇ), where ʙʟᴜᴇ actually is a set of RGB datapoint. There are 79 unique reference labels (like ʙʟᴜᴇ) and 81 unique comparatives—relatively slim pickings.

The authors make a poor assumption: that you can simply compare the averages of the sets to learn the positions. With that, all you’d need is to average each cluster and compute a vector from centroid to centroid. :-/

Hey, while we’re on silly things that this (somehow) ACL best paper did—RGB coordinates were used in the data collection, sure, but using them to find the vectors encoding the comparatives is relatively meaningless—the distances in RGB space don’t align with perceptual judgments of similarity.

Aaaand now for some reason, since this is an ACL paper, we have to work Word Embeddings into it. We evidently use these to condition our vector on the input word. This is what gives the model an ability to predict new vectors. (But this assumes you a priori know the general category labels and their coordinates.)

The bottom line

Nobody has done work on grounding comparatives before, the authors contend. But isn’t a comparative only meaningful in the context of a reference color, so we open the door to massive overfitting. This paper feels like a fun blog post, and I’m sure the color and examples made it eye-catching. But there’s not a whole lot of meat to it.