Translating Pro-Drop Languages with Reconstruction Models

(Wang et al., 2018) at AAAI

Translating from pro-drop languages to non-pro-drop languages is a challenge. How do you synthesize the implied information, when your model can only think on the level of words, not grammar? If the bread is delicious, you want to ask, “Did you bake it?”—not “Are you baked?”

Today’s paper presents a two-step process for doing this: automatically add the dropped pronouns back into the source, then use a multi-task model to predict both the annotated source and the translation from the original source.

Pro-drop is an economical way of saying a language “drops” its “pronouns”. When the subject can be inferred from context, you don’t need to give it. In Spanish, you can say “corro” instead of “yo corro”, because the conjugated verb “corro” encodes the subject.

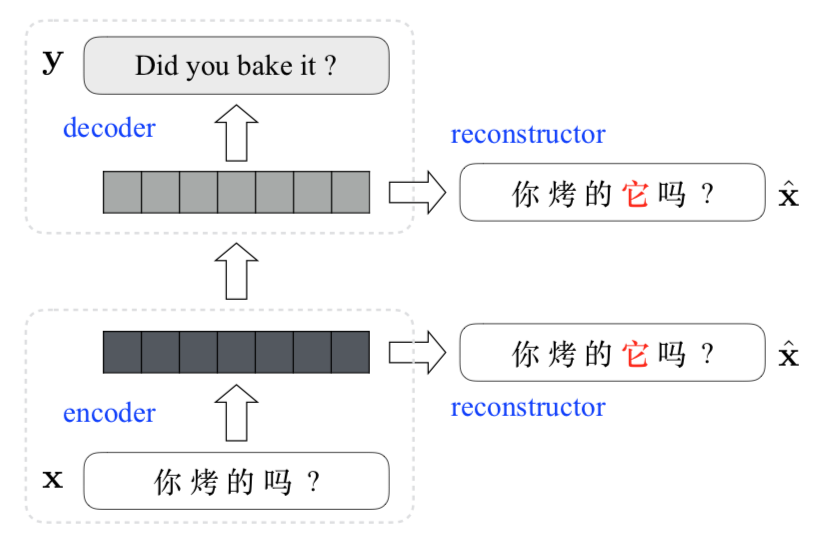

Step one of their model is to turn each (x, y) tuple into an (x, y, x̂) triple by incorporating a label for each dropped pronoun in the source. Step two is to translate with a recurrent encoder–decoder. The hidden states of the encoder and decoder are now inputs to a reconstructor that works to generate x̂.

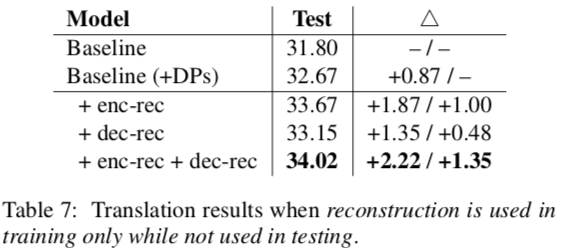

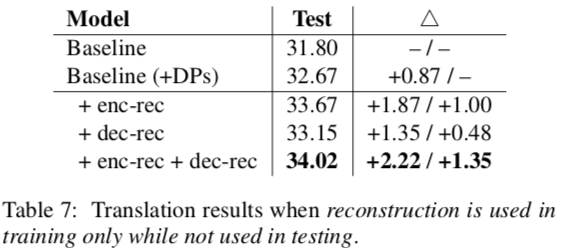

Even when only applying the reconstruction during training, it results in better performance. Decoding was just as fast, but BLEU went up by 1.35 points. Adding it during test, too, gives another 1.06 points.

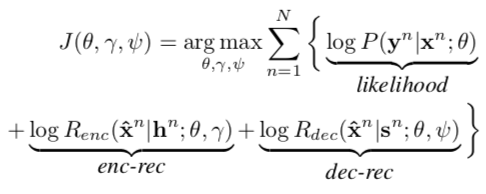

They use two objectives. One is to maximize the likelihood produced by the encoder–decoder. The other is the reconstruction loss.

So what is reconstruction? It’s a way of getting the source back out from a latent representation. It reads a sequence of hidden states and a pronoun-labeled source, then scores how well that labeled source can be produced. It seems like another seq-to-seq model that shares the encoder (and optionally the decoder) with the main MT model, but this one is used to try annotating the pronouns. They also share word embeddings between x and x̂.

If you attach the reconstructor to the encoder, you get an auto-encoder. Its hidden states not only summarize the source, but also embed information about DPs. If you attach it to the decoder, as in Tu et al., you get the labeled source out instead of a translation.

Their data is more than two million sentence pairs pulled from subtitles.

They use a neural model for monolingually labeling the DPs, because these labels aren’t available during test time.

Decoding is only 18% slower because “No beam search is required for calculating reconstruction scores.” How’s that? It’s because you already have the reconstructed sentence as part of the problem instance. You’re just calculating the probabilities of each successive word in it being generated by the model.

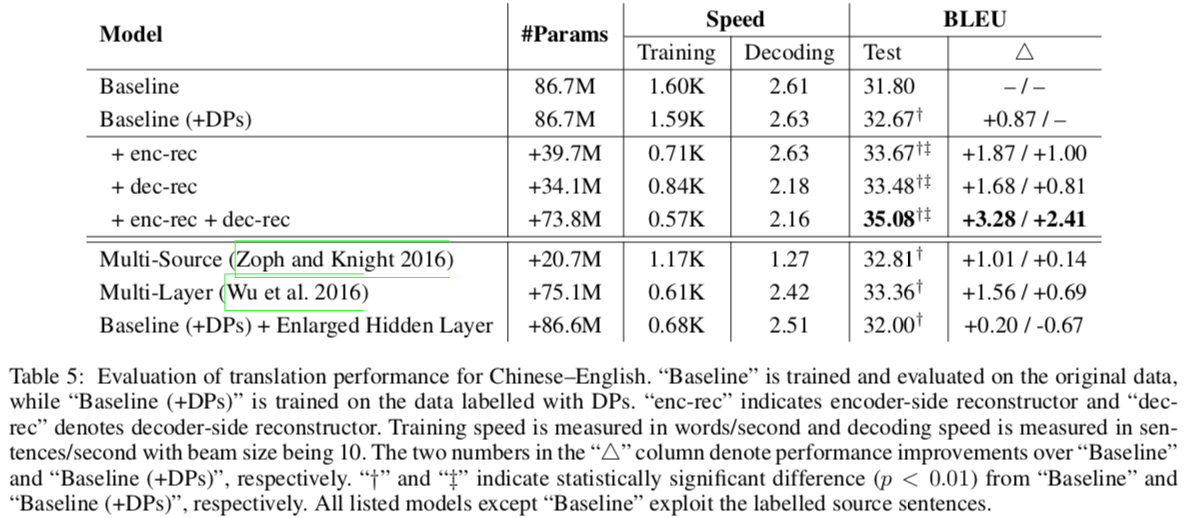

After showing that their model was sunshine and daisies, they compared the translation of their model to one which only used labeled DPs during training. Better than the baseline, but not fantastic.

They compared to other work to show that it’s not just the number of parameters that’s helping them. Wu et al. had three-layer encoders and decoders, but still didn’t do as well. They also tested a baseline model with just a huge hidden layer.

We found that the multi-layer model significantly outperforms its single-layer counterpart “Baseline (+DPs)”, while significantly underperforms our best model (i.e., 33.46 vs. 35.08). The “Baseline (+DPs)” system with enlarged hidden layer, however, does not achieve any improvement. This indicates that explicitly modeling DP translation is the key factor to the performance improvement.

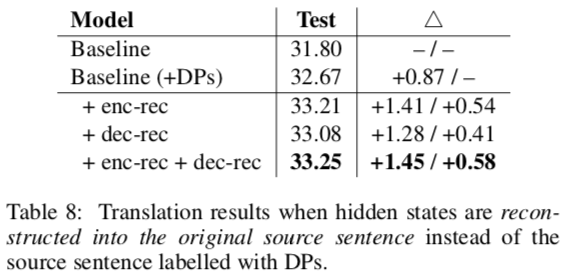

To see whether the improvement came from dual learning, they altered their reconstructors to yield the source sentence x instead of the labeled sentence x̂. None of these performed as well as models that explicitly sought to model DPs.

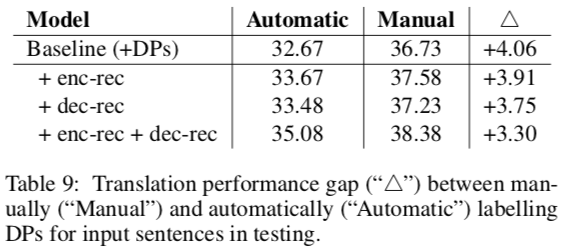

A last comparison is how much manually or automatically annotating DPs improves scores. The authors found that manual labeling of their test data gave good results; have they tried joint learning? (Even more params, yikes.)

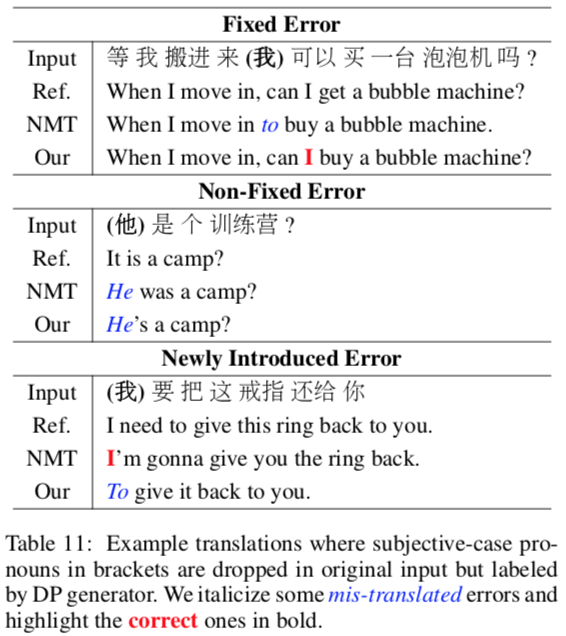

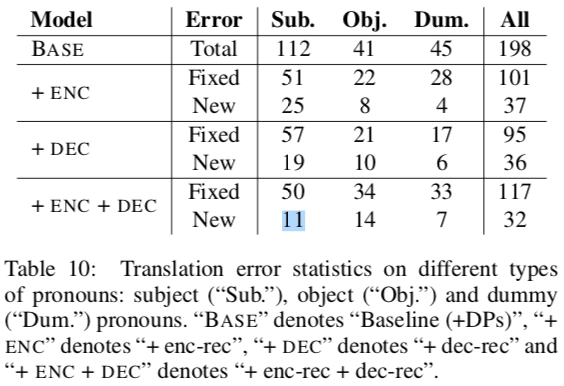

In their error analysis, they showed that they handle object pronouns and pleonastic “it” (“it is raining”) well. They didn’t handle subjects quite as well, and sometimes they’d push in subjects that didn’t even exist.

EDIT: for those of you that care, this is an instance of multi-task learning. Shared representations learn to produce the reconstructed sentence (in two different places) and the target sentence. This acts as a form of regularization.

The bottom line:

- Training MT with a reconstructor that explicitly models dropped pronouns improves scores.