Found in Translation: Reconstructing Phylogenetic Language Trees from Translations

(Rabinovich et al., 2017) at ACL

I’m starting a new thing where I write about a paper every day, inspired by The Morning Paper. Let me know what you think.

Today’s paper addresses the question of whether the act of translation or the source language has greater effect on the resultant translation. They go so far as to claim:

The signal of the source language is so powerful that it is retained even after two phases of translation.

Exploiting this, they recreate the phylogeny of languages using only monolingual data. This is interesting from a historical linguistics perspective, and it’s also useful for native language identification (NLI).

The authors begin by identifying some universal trends in translation: simplification of structures, conformance to target standards, and greater overtness. This is contrasted with “interference” introduced by the source language, which prevents us from simply translating the concepts through some interlingua. Interference is a property of the language pair, because target languages which don’t share structures with the source must resort to circumlocutions to express the same idea. More evidence for this comes from the fact that original-vs-translation classifiers don’t generalize well from language to language.

Measuring the number of similar structures for a language-pair’s translations gives a distance. These distances can be used by some hierarchical clustering algorithm—might I recommend mine?—to build up a phylogenetic tree.

The big takeaway of the paper is that interference structures are strong enough to create these phylogenetic trees and group languages together. This text-driven approach differs from Shu et al. (2017), who a catalog of language features to compute trees.

Their approach leverages Europarl, proceedings of the European Union’s parliament. All content is required to be presented in the 21 member languages, and they use English as an intermediary when translating. (This reduces the parliament’s demands for translators: they only need people who can translate into and out of English—O(n), as opposed to all language pairs—O(n^2).)

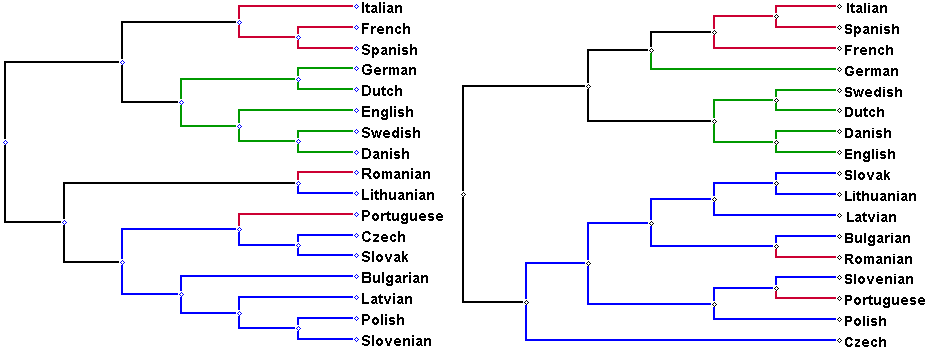

From this data, they computed trees based on each of two interference features and one universal feature:

- Shallow syntactic structure in the form of most-frequent POS trigrams

- Function words

- Cohesion markers, which proliferate because of the universal tendency toward overtness when translating.

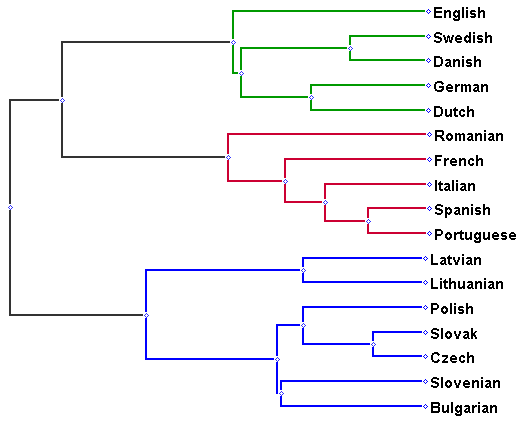

This is compared to the “true” tree of Serva and Petroni (2008).

The authors scaled their data and clustered it using Ward’s method. They ignore a bunch of flawed scoring metrics. Their simple measure, based on the L2 norm, is the sum of squared deviations between each pair’s gold-tree distance and computed distance.

\[Dist(T, g) = \sum_{i, j} (D_T(l_i, l_j) - D_g(l_i, l_j))^2\]A sample tree from their results, translating into English and then further into French, are produced below. It’s interesting that Portuguese and Romanian keep winding up with the Balto-Slavic languages. Romanian has a lot of structural differences from the other Romance languages—postfix definite articles, a still-living case system—and its geography opens it to cross-pollination with the other languages of the Balkan sprachbund. (The authors also note this in their conclusion.) Portuguese has phonological similarity to Romanian, but that’s certainly not captured by any of the three features; I wonder why it also got misplaced.

Even the source→English→French tree looks pretty good, so strong indicators of the source language are continuously propagated.

Digging into the details of why their results stood, they looked for the rates of certain phenomena in the English translations. One example is the use of the “of X” construct for possession, produced by interference because English allows the “-’s” clitic but Balto-Serbian and Romance languages don’t. These continued to be indicative. Another is phrasal verbs (“turn down”, “come over”) that are prevalent in Germanic languages. The Germanic→English translations also had more of these, as expected.

They also confirmed the ease of discriminating between original texts and translations using a linear SVM and 10-fold CV. They got high-90s accuracy for POS trigrams and function words—the interference features—but cohesive markers—a translation universal—performed about 10 points worse.

One concern that both this paper and the Shu et al. (2017) paper raise for me is that their phylogeny work focused on the same three European language families and nothing else. There’s a centuries-old tendency in linguistics to be Western-world myopic, and these papers suggest a computational continuation of the trend.

Also, a colleague told me yesterday that there’s been no worthwhile work in computational historical linguistics in the last thirty years. But this ACL paper is the second I’ve seen that concerns itself with the phylogeny of languages.

As I pointed out above, the big takeaway here is that superficial parts of languages are carried into translations. The signal is so strong that the authors managed to largely reconstruct the phylogenetic structure of languages just using English text with different sources, and even source→English→French text. The implication here is that we may be able to determine the original languages of translated documents, like early books of the Bible, from the forms they take on today.