Multi-Agent Cooperation and the Emergence of (Natural) Language

(Lazaridou et al., 2017) at ICLR

Remember when Google had two computers devise a crypto system that humans can’t interpret? There are other multi-agent games that can find useful coding of information. This paper presents a model of two agents who learn to describe images to each other, as well as how to turn those messages into natural language.

Spoiler: I’d hardly call what it generates “natural language”. It labels images. With single words.

Rather than training on large amounts of text (or an even more IR-based approach of pulling sentences from a bag), the authors wanted to have two agents learn to communicate by communicating. Here, two agents need to coordinate to receive higher rewards, so they bootstrap off each other’s knowledge.

There are two questions that jump out:

- Can you really learn to communicate from tabula rasa? This has been a long-standing question in cognitive science, and the paper may give hints at the answer.

- Will these agents’ communication resemble human language?

Their results say yes. In the game, a sender has to correctly convey which image from a finite vocabulary was observed, and a receiver has to interpret the message. Both receive the same reward: 1 if the recipient got it right, or 0 if the recipient got it wrong. After 1000 rounds of back-and-forth, the agents are nearly perfectly coordinated.

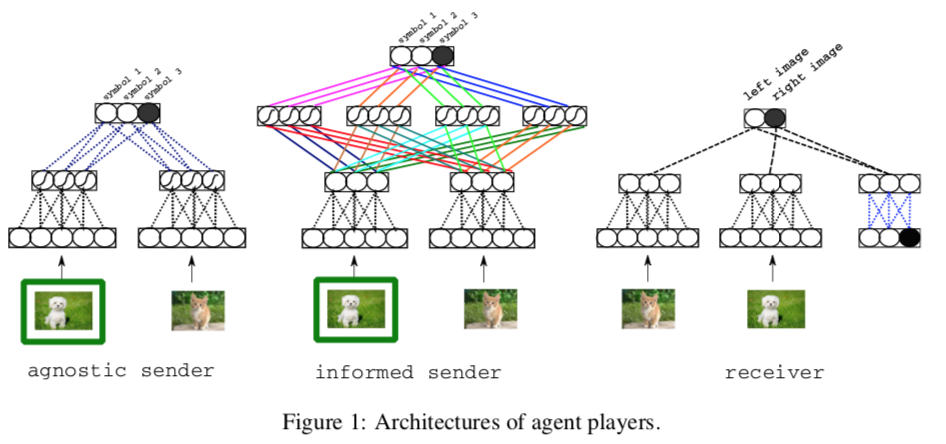

Their sender architecture performs sigmoidal (and optionally convolutional) sorcery to embed the image and a distractor image, then ends with a softmax distribution, which is sampled to select the right symbol from the vocabulary. The receiver takes both images (shuffled) and the sender’s symbol, embeds all of them, then uses dot-product similarity to assign weights to each image. The weights are fed through another softmax, which gives another probability distribution to sample.

(They differentiate here between an informed and agnostic sender. One has some fun convolutional layers that manipulate the image pairs; the other simply takes representations of each image and makes a decision. The agnostic model only uses two symbols, which amount to “light” and “dark”.)

To check redundancy in symbol usage, the authors constructed a matrix of (image pair, symbol) tuples, then decomposed it with PCA. It’s not every day that I see a scree plot (the spectrum) in an NLP paper, so I’m a bit excited. Wonder why, though, they didn’t use parallel analysis to see which PCs were important. It looks like at least 10-15 PCs were significant, just going by the Cattell test. That’s a pretty big space, given that the American electorate can be comfortably described by two dimensions. But their claim, “the first few dimensions do capture only partial variance” is dubious.

Now the sending agent gets trained differently, interleaving the learning of image classification into a finite vocabulary. This makes it use a broader vocabulary of symbols before, and the symbols are much more pure—it uses certain symbols only for certain images. Because many symbols now correlate with images or concepts, they can be interpreted.

Finally, they ran a test on human subjects. They gave humans the output “word” that matched with the output symbol, plus the two images, and had humans guess which image was correct. The humans got 68% right. That’s a bit better than chance, isn’t it?

The bottom line:

- The neural Lewis game is a good way for agents to learn associations between images and words.