Decoding Anagrammed Texts Written in an Unknown Language and Script

(Hauer and Kondrak, 2016) in TACL

What mysteries does the Voynich Manuscript hold? Its unknown writing system has tantalized linguists for a century. Today’s paper makes some informed judgments about the language it might be written in, as well as presenting a more general pipeline for deciphering unknown text. Their results show that Hebrew is an outlier among the languages they test, suggesting the most probable language for the text.

Radiocarbon dating puts the Voynich manuscript’s age at around 600 years. It’s written in a mystery script, which could take on any of the properties of normal text, plus additional encipherment of its information. Different analyses have suggested similarities to Latin, Italian, German, Spanish, English, Moldavian, Thai, Arabic, and Chinese pinyin.

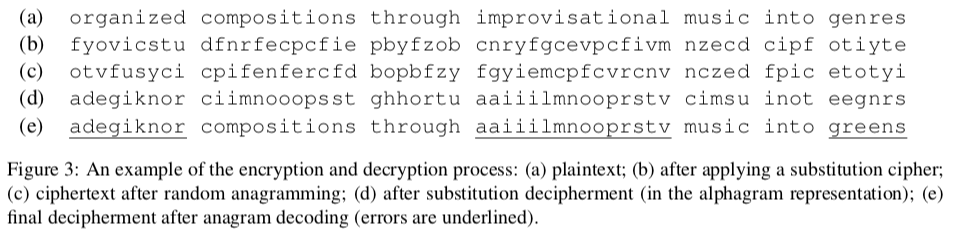

Hauer and Kondrak assume that the text is anagrammatic, based on an observation of fixed ordering within words by Tiltman (1968) and later the suggestion of alphagrams (alphabetically ordered anagrams) by Rugg (2004). The character sequences have unusually predictable sequences.

One step to interpreting the text is knowing its language. While language ID is a studied problem, it’s complicated in this circumstance by the cipher (believed to be) applied to the text.

One way of identifying this is character frequency—each language has its own signature of how frequent each letter is. In English, the distribution of characters approximately follows the pattern ETAOIN SHRDLU…, while in Romanian, they follow the pattern AIELURT…. The authors draw their frequencies from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 380 languages. (This seems fishy, because the language isn’t in the normal register. Perhaps at the character level, this doesn’t matter as much, but in English, the register exhibits a preference for Latin-origin words. This may mislead the second model below.)

A one-to-one character substition is a cipher that wouldn’t alter these distributions; this is a common codebreaking technique. This can be exploited by computing the frequency distribution for the mystery text and comparing it to candidate languages’ distribution. Under the authors’ assumption of an anagrammatic cipher, the frequency distributions are still unchanged.

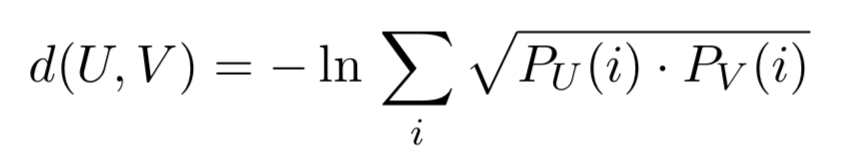

They use the Bhattacharya distance between the distributions U and V (which are categorical). It uses the agreement between the assigned frequencies for each character i:

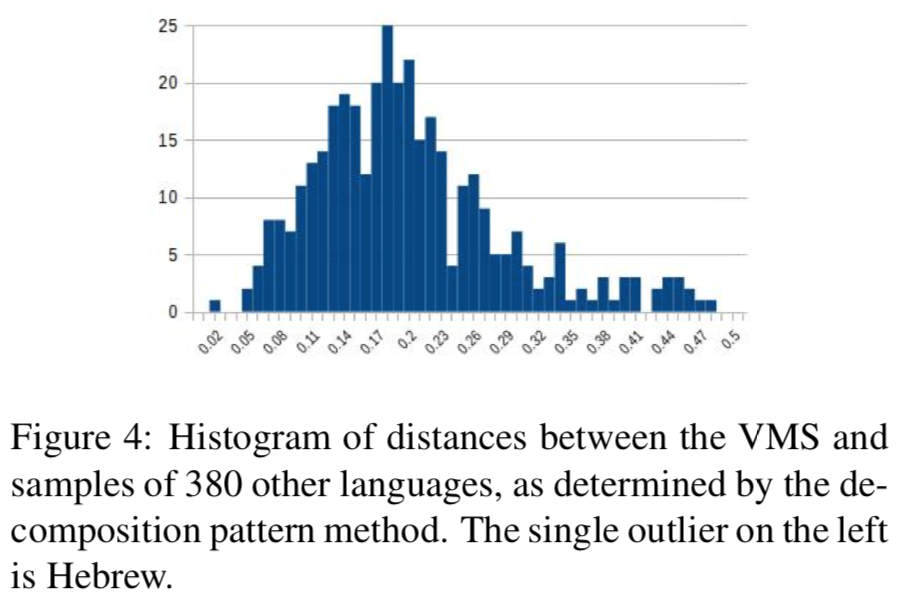

Another model they attempt relies on decomposition patterns. The decomposition pattern of the word assesses, for instance, would be (5, 2, 1), a sorted reflection of the counts of each letter. Now, instead of on character frequencies, they compute the Bhattacharya distance on decomposition pattern frequencies. (Decomposition patterns are personally interesting because I use them to prove a property of scoring functions on sets.)

A third model they attempt is a greedy swapping algorithm: begin with an initial alignment between the character sets of the text and the candidate language, then change the alignment to improve symbols which show up in rare bigrams.

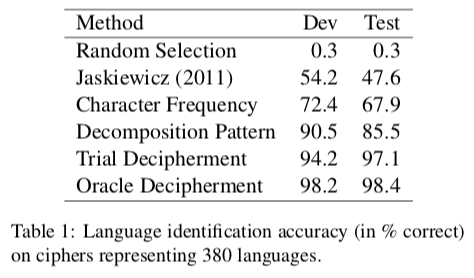

The increasingly complex models do better at language identification on the UDHR, but again, this seems suspect to me—they use the same domain for training and testing, and there’s no reason to suspect that the Voynich manuscript is in the same domain.)

To actually decipher the script, they evaluate using word-level language models, falling back to character-level models for out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words. The process has three parts:

- Key scoring

- Key mutation

- Tree search

For mutation, they swap through the set of possible words in a position that have the same pattern decomposition. Their method has an error rate of 2.6%. They finish their decoding with an HMM whose states are the words in their vocabulary and the sequences are alphagrams. With a Viterbi decoder, they pick the most likely word for the alphagram (or unknown, if it’s unseen).

The authors also rerun their pipeline without vowels in their decoder, so that they can recover the original text.

They note that they need a bigger test vocabulary than the UDHR, so they use Wikipedia articles from various langauges to try IDing languages. They note that of their three types of errors (decipherment, decoding, and OOV), OOV errors are the most frequent. The decoder only produces observed words, so compounding (and declension) may be the causes of low performance.

At long last, having shown that their pipeline works, they run their model on the Voynich manuscript. They find that the decomposition patterns in the manuscript are incredibly close to Hebrew, with Malay as a distant second. It’s actually an outlier in the distance space, compared to other languages. Hebrew was also a common written system at the time, and cipher techniques like anagramming came from the Jewish community.

Finally, the paper attempts to perform a greedy search in the space of orderings to find the letter order of the alphagrams. (The authors note that the decision problem is NP-hard.) They find that the average deviation from the alphagram ordering they compute is 0.996, which is only about 40% of the deviation for English—a strong suggestion that there is an alphagrammatic cipher. With this, they can attempt to decipher.

The first line of the VMS (VAS92 9FAE AR APAM ZOE ZOR9 QOR92 9 FOR ZOE89) is deciphered into Hebrew as המצות ועשה לה הכה איש אליו לביחו ו עלי אנשיו. According to a native speaker of the language, this is not quite a coherent sentence. However, after making a couple of spelling corrections, Google Translate is able to convert it into passable English: “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.”

…We restrict the word language model to unigrams…from the “Herbal” section of the VMS, which contains drawings of plants. An inspection of the output reveals several words that would not be out of place in a me- dieval herbal, such as הצר ‘narrow’, איכר ‘farmer’, ’fire‘ אשׁ ,’air‘ אויר ,’light‘ אור.

The spelling discrepancies are excusable to me, because language wasn’t always so forcibly consistent in its spelling. (See James Gleick’s The Information.) It’s reasonable to suspect that this is a Hebrew dialect or some related language. (Though, the authors only operated on languages they had the UDHR for…What about deader languages?)

The work made some strong assumptions about the nature of the cipher, and they present options of line-to-line transpositions and generative modeling as potential future directions. Still, to have such a strong signal in favor of Hebrew is a worthwhile first step in the decipherment process.