Diachronic Word Embeddings Reveal Statistical Laws of Semantic Change

(Hamilton, Leskovec, and Jurafsky, 2016) at ACL

Today’s paper looks at how meanings evolve. The authors claim to have uncovered two laws of semantic change. The first is the “law of conformity”: the rate of semantic change scales inversely with frequency. The second is the “law of innovation”: meanings change faster in words with more senses.

For background, we know that some phenomena occur more in high frequency words than in other, and we know that more frequent words have more senses. But we don’t know how either of these relate to semantic drift.

To analyze this, the authors construct embeddings (fixed-length vectors representing each word) by three different methods, then align those of the same type from decade to decade.

Their methods are:

- PPMI, or positive point-wise mutual information. They smooth it and rectify the PMI, such that only positive correlations are emphasized. (This makes sense, because your corpus might just not be big enough to show the two words together.) It also assumes a pre-built list of context words. Each row in the matrix M is the PPMI between the given word and the context word.

- SVD. SVD is the math behind principal component analysis. They apply this as a dimensionality reduction of the PPMI matrix: M = USV*. (They keep the scores on each dimension US, rather than the directions V.) Because they only keep a fraction of the dimensions, it acts as a regularizer.

- SGNS (i.e. word2vec). Word2vec is its own conceptual disaster, but very popular and quite successful. It’s useful in this case because you can initialize the embeddings for a time period t with the embeddings from the previous time period t - ∆, helping you better model the transitions. (They borrow this idea from Kim et al. (2014), who first used word2vec (a “neural model”) to study diachronic meaning change.)

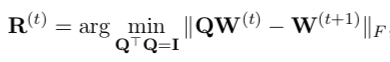

The SVD and SGNS methods both produce a vector space representing all words as vectors. But these vector spaces can be oriented arbitrarily: If you perform one of these methods for two consecutive decades, you will get different vector spaces even though most words’ meanings are similar. If you want to compare the embeddings across decades, then, you have to rotate one vector space so that they can be compared properly. (PPMI is inherently aligned because you use the same context words in all years to define the columns.) The technique to align the vector spaces is called Procrustes (jokingly named after this maniac). It finds the orthogonal rotation Q of W_t that minimizes its difference from W_{t+1}.

I admire how the authors gamed the Spearman correlation coefficient to detect pairwise meaning shifts. If the similarity values s1, s2, …, sn correlate (positively or negatively) with the time values t1, t2, …, tn, then there’s been a meaning shift.

The authors worked on both the Google N-Grams corpus and the COHA corpus, which is supposed to be extremely well-balanced and representative of American English. They evaluate diachronic embeddings in two ways:

- Detection: when mining shifting words from a corpus, what recall are they able to achieve on a list of words with known directional shifts?

- Discovery: self-judging the top 10 words each method shows as having shifted, according to that Spearman sorcery. (That fact makes me uncomfortable. Also, reporting 70% is not cool when it’s 7 out of 10.) SGNS wins, then SVD, then PPMI.

Also, good to know: for (synchronic) word similarity, SVD performs best. For word analogy, SGNS performs best.

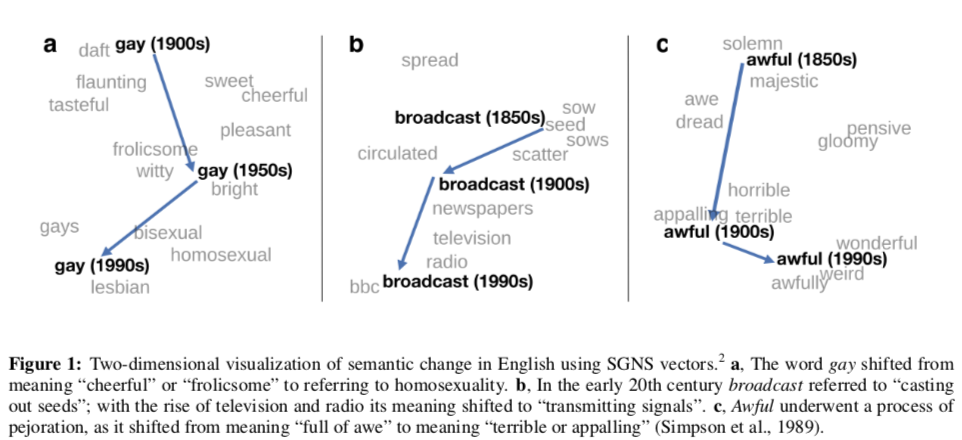

These results suggest that both these methods are reasonable choices for studies of semantic change but that they each have their own tradeoffs: SVD is more sensitive, as it performs well on detection tasks even when using a small dataset, but this sensitivity also results in false discoveries due to corpus artifacts. In contrast, SGNS is robust to corpus artifacts in the discovery task, but it is not sensitive enough to perform well on the detection task with a small dataset. Qualitatively, we found SGNS to be most useful for discovering new shifts and visualizing changes (e.g., Figure 1), while SVD was most effective for detecting subtle shifts in usage.

Now we get to the unveiling of their “laws”. They examine these by looking at the rate of change of the word’s meaning; that is, what is its similarity to the same word in the previous decade? From here on, they stick to word2vec (SGNS) vectors. They ask how a word’s polysemy and frequency predict its future position. (One thing word2vec is bad at is polysemous words. You get a triangle inequality problem: the word pulls each of its senses closer together, even though they’re unrelated.)

With SVD embeddings the effect of frequency is confounded by the fact that high frequency words have less finite-sample variance in their co-occurrence estimates, which makes the word vectors of high frequency words appear more stable between corpora, regardless of any real semantic change. The SGNS embeddings do not suffer from this issue because they are initialized with the embeddings of the previous decade.

With this in place, they create a linear model to compute an adjusted score, based on the frequency polysemy of each word along with effects from the decade itself, including random intercepts for each word and random noise at each time point. Interpreting this is dicey—they claim to find power laws out of an equation that only allows for power laws. Without credible intervals on the weights, this could have been anything.

More interesting is how they look at polysemy. They compute it as the negative of the local clustering coefficient (hooray network science!), which is essentially the triangle density of a node: how many triangles is it a part of, out ot the total number that could exist given its incident edge set? So more clustering means fewer senses. Evidently this has been shown to correlate with WordNet senses. Unfortunately, it also awards points to function words.

At the end of their pipeline, some hand-waving gives you the laws of conformity and innovation, which I gave away in the introduction.

These empirical statistical laws also lend them- selves to various causal mechanisms. The law of conformity might be a consequence of learn- ing: perhaps people are more likely to use rare words mistakenly in novel ways, a mechanism for- malizable by Bayesian models of word learning and corresponding to the biological notion of ge- netic drift (Reali and Griffiths, 2010). Or per- haps a sociocultural conformity bias makes people less likely to accept novel innovations of common words, a mechanism analogous to the biological process of purifying selection (Boyd and Richer- son, 1988; Pagel et al., 2007). Moreover, such mechanisms may also be partially responsible for the law of innovation. Highly polysemous words tend to have more rare senses (Kilgarriff, 2004), and rare senses may be unstable by the law of con- formity.

Also interesting to me about this paper is their visualization technique. It builds on the t-SNE nonlinear embedding method to show how a word’s meaning has changed:

1. Find the union of the word's

$k$ nearest neighbors over

all necessary time points.

2. Compute the t-SNE embedding

of the words on the modern

time-point.

3. For the previous time points,

hold embeddings fixed, except

the target word's. Optimize a

new embedding for the target

word.

The authors note that the procedure shows all words in their modern positions. I accept that it’s more useful to us who know these words’ modern senses, but only if a large number of reference words haven’t changed in meaning. Also, the last step is pretty unclear.

The useful tricks:

- Spearman correlation of a metric with time to show whether there’s a drift

- Procrustes projections for aligning two vector spaces

- SVD for capturing analogical relationships

- Counting the number of families a node takes part in using the local clustering coefficient.

EDIT 2018-02-22: There’s a post from The Morning Paper, out today, that talks about a response to this work. Instead of aligning word embeddings using Procrustes, they jointly optimize both the embeddings and the alignment. They include a loss term that computes the difference between the embeddings for consecutive time periods, without rotation, when learning the optimal embeddings. This lets them perform diachronic analogy tasks: the nearest neighbor to the 2016 value of obama is always whoever is the President that year.