Non-distributional Word Vector Representations

(Faruqui and Dyer, 2015) at ACL

(Busy day, so I’m looking at a short paper!)

This paper is a critique of word vectors. Because word vectors are difficult to interpret, the authors present extremely sparse word vectors drawing from known semantic and syntactic resources. If your language has the resources to make these vectors, they’re inexpensive to produce. They’re clear, and they’re competitive.

Everything is neural now. Neural networks operate on numbers, though—not words. Algorithms like word2vec can create extremely dense numerical representations of a word, operating on the distributional hypothesis: “You will know the meaning of a word by the company it keeps.” The contexts of semantically similar words should be similar.

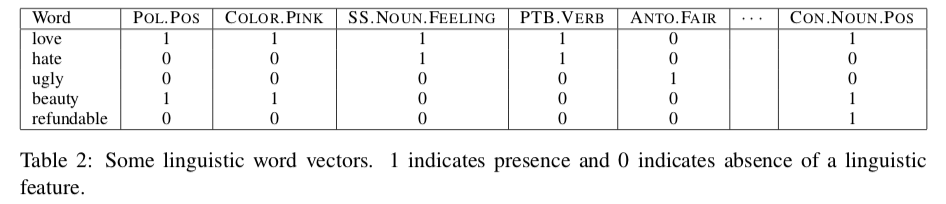

What if, instead, we leveraged existing information compiled by linguists? Instead of a distributional representation—one relying on the co-occurrence of words—we have an extremely long binary vector. Each position’s 0 or 1 represents the absence or presence of the given linguistic feature. Each index in the vector has a meaning, so they’re fully interpretable.

Distributional vectors are created by training your…embedder?…on billions or hundreds of billions of tokens. By contrast, linguistic resources like WordNet have only tens of thousands of words. This is five to seven orders of magnitude smaller! Assuming you have the database available to you, this should make the construction of vectors radically faster.

The resources they use are:

- Wordnet. There’s a lot to mine from here. Membership in each WordNet membership group is one bit. Antonyms and pertainyms are also used; I imagine pertainyms make a good substitute for distributional vectors, because it implicitly conveys co-occurrence.

- Supersenses. Broad categories of nouns, verbs, and adjectives based on WordNet.

- FrameNet. Information about verb arguments. Verbs with similar frames should be related.

- Emotion and Sentiment. Is the word positive or negative? Which of eight emotions does it relate to?

- Connotation. The polarity of the nuanced sentiment, as opposed to its dictionary definition.

- Color. Straightforward, if weird. What colors are things?

- Part of Speech. Pulled from the Penn Treebank.

- Synonymy and Antonymy. Did they seriously cite the 1852 version of Roget’s thesaurus? Yes. Marking which words are synonyms of others gave 75,000 features.

The resulting vectors have about 170,000 dimensions but only 34 nonzero features on average. Sparsity makes storage efficient—these vectors are far more compact than typical 300-dimensional distributional word vectors. These vectors get squeezed down to a similar size to the distributional vectors by SVD, the math behind PCA.

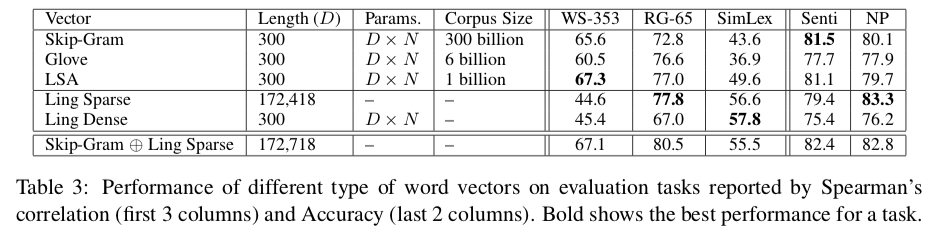

The competitors are:

- Skip-Gram word2vec trained on 300 billion words

- GloVe trained on 6 billion words

- The SVD of a co-occurrence matrix, trained on 1 billion Wikipedia words, using a window of 5 words on each side.

The sparse and dense linguistic vectors, along with the three distributional vectors, were used for three downstream tasks. On three versions of the word similarity task, the sentiment analysis task, and the NP-bracketing task, the performance was comparable. Except for one similarity version, the linguistic vetors were either the top or within a few points of thop. On top of this, they concatenate their linguistic vectors to skip-gram and show hat it consistently improves on skip-gram’s performance.

If computationally cheap-to-produce vectors based on existing knowledge work so well, then why would there be any reluctance to adopting them? First of all, these huge resources only exist for a handful of languages. Distributional vectors, on the other hand, don’t need any labeled data. Also, the linguistic vectors don’t have any ability to generalize to unseen words: if it’s not in the database (or the word has picked up a new sense), you can’t work with it.

Curious future direction: Could you use MT to align category labels in different languages? Let’s say there’s a French version of WordNet. Train an MT system to learn a dictionary. Use a comparative-method-style set agreement procedure to align the sets of categories for each word.

The bottom line: when you have lots of labeled data for a language but not a lot of time, linguistic vectors are a strong option for vectorizing words, and they perform well in downstream tasks. Plus, they’re easy-to-understand.