The Comparative Method and Linguistic Reconstruction

(Campbell, 1998). From Historical Linguistics: An Introduction

Today, we’re going in a different direction: a dive into the past. We’re looking into how linguists create the phylogenetic relationships between languages, as well as how they reconstruct the proto-languages that turned into our present-day tongues.

In NLP, one might ask why we care about reconstructing proto-languages. Well, because we’re scientists, not engineers. It’s all in the pursuit of truth. The tool of our scientific endeavor is the comparative method. It examines the speciation process of languages. We’ll frame our discussion with some terminology:

- Proto-language: that from which other languages are derived; also the reconstructed progenitor. The goal of reconstruction is to minimize the divergence.

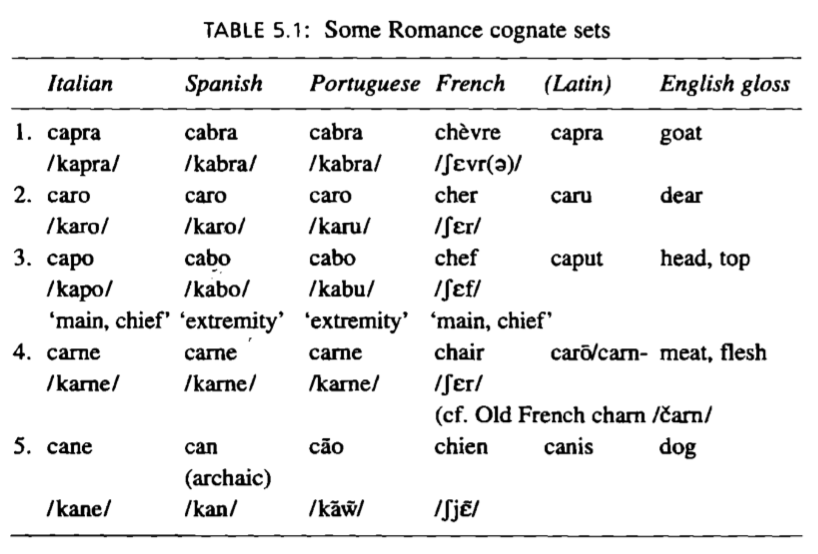

- Cognate: A word or morpheme—word subunit with meaning—with a common ancestry in multiple languages.

- Cognate set: The set of cognate manifestations of a progenitor in the descendent languages.

- Sound correspondence: Same as cognate set, but sounds.

- Reflex: descendent of original sound. It reflects the original sound. Usually it’s harder to recover these because there’s no written record.

With that in mind, the comparative method is a seven-step process for reconstructing the phonemes of the ancestor from cognates.

-

Assemble cognates A popular form for these is Swadesh lists. They are tables of “core vocabulary” in languages. They’re named after Morris Swadesh, an exemplar of why you shouldn’t generalize outside of your domain. He saw regularity in how often the “core vocabulary” changed, but he only looked at Western European languages. His observations didn’t hold for other languages.

Borrowings and false friends can confuse your cognate lists.

Badin English andbadin Persian both mean bad, but they’re unrelated. And as I noted previously, the Japanese word for computer is a borrowing, not a cognate.

- Establish sound correspondences Having a large list of cognates will eliminate coincidences. (This is a massive multilingual alignment task.)

-

Reconstruct the proto-sound

Eventually you have to use these alignments. There are four tricks to help decide the proto-sound given the descendent sounds:

- Directionality. Looking across all the world’s languages, some sound changes have historically only occurred in one direction. For instance, intervocalic voicing of stops. Also, French went k -> ch -> sh, and English borrowings (chief, Charles) came in the middle.

- Majority wins. Superficially clear, but there’s some danger. What if everyone undergoes a common sound change? Also, we need the majority to be fair. What if you’re deciding based on Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician? The last two are much more related. (Could you do alternating optimization over trees to decide a weighting for each language, derived from the similarity, then use that weighting to recompute similarity?)

- Factoring in features held in common. Which aspects of sound (voicing, location, etc.) are held in common across languages? Those were probably in the parent.

- Economy. You prefer a parsimony in the number of steps. It’s Occham’s Razor, and geneticists use it, too: if something changes, assume it changed only once.

-

Determine the status of similar (partially overlapping) correspondence sets

Sometimes, two different hypotheses both reconstruct the same phoneme. Sound change is regular, so is it based on the particular position of the phoneme in relation to other sounds, or is it really two separate sounds in the ancestor?

As an assumption, however, the postulate [of sound-change without exception] yields, as a matter of mere routine, predictions which otherwise would be impossible. In other words, the statement that phonemes change (sound-changes have no exceptions) is a tested hypothesis: in so far as one may speak of such a thing, it is a proved truth.

In French, the change was conditioned on context. When you don’t have that, you need to assume different ancestor phonemes.

-

Check the plausibility of the reconstructed sound from the perspective of the overall phonological inventory of the proto-language Now we need to look at the focalization and dispersion of the vowels, as well as the symmetry of the consonants. We want some congruency in the pattern.

- Check the plausibility of the reconstructed sound from the perspective of linguistic universals and typological expectations Languages need vowels. Languages with nasal consonants will have their non-nasal counterparts. Et cetera.

- Reconstruct individual morphemes Use your phoneme-to-phoneme alignment and translate into the progenitor sounds.

In performing the phoneme alignments, there are some regular patterns to consider:

Grimm’s Law (Germanic)

Voiceless stops -> voiceless fricatives Voiced stops -> voiceless stops Voiced aspirated stops -> voiced plain stops

Grassmann’s Law (Sanskrit and Greek)

The first of two aspirated stops loses its aspiration.

Verner’s Law (Germanic)

In PIE, when the accent followed, medial voiceless stops and fricatives became voiced.

The three of those put together feel like boosting—each fixed the missed cases in the one before it. They are almost completely inviolable. In fact, taken together, the regularity of sound changes has been lauded by neogrammarians: “One of the most significant conclusions in the history of linguistics.”

A note on the assumptions:

The method makes four:

- The proto-language was uniform with no variation.

- Language splits were sudden.

- There was no contact after the split.

- Sound change is regular.

Assumption 1 is an idealization, because what else do we have? We don’t have records about these people’s language, or we wouldn’t need to reconstruct them. And 2 and 3 are mainly to make the tree construction easier.

How realistic are the results?

If we just went off what we see in the daughter languages, we wouldn’t know some of the things they deleted. But isn’t it great how much we do get? Also, we don’t get any idea about the syntax or semantics of the ancestor—just its morpheme and phoneme vocabulary. And really, we only get that for words in the core vocabulary, in languages with a large number of living descendants. But it’s the best we have, and it’s a glimpse into our past.