Synthetic and Natural Noise Both Break Neural Machine Translation

(Belinkov and Bisk, 2018) at ICLR

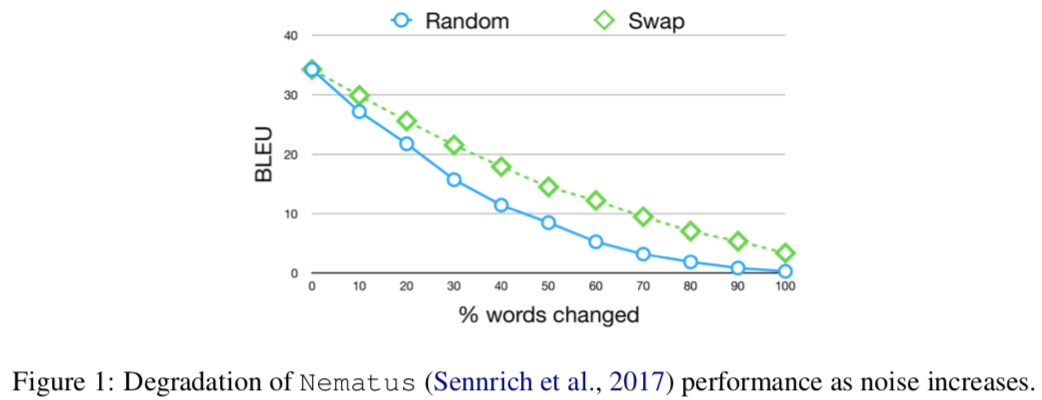

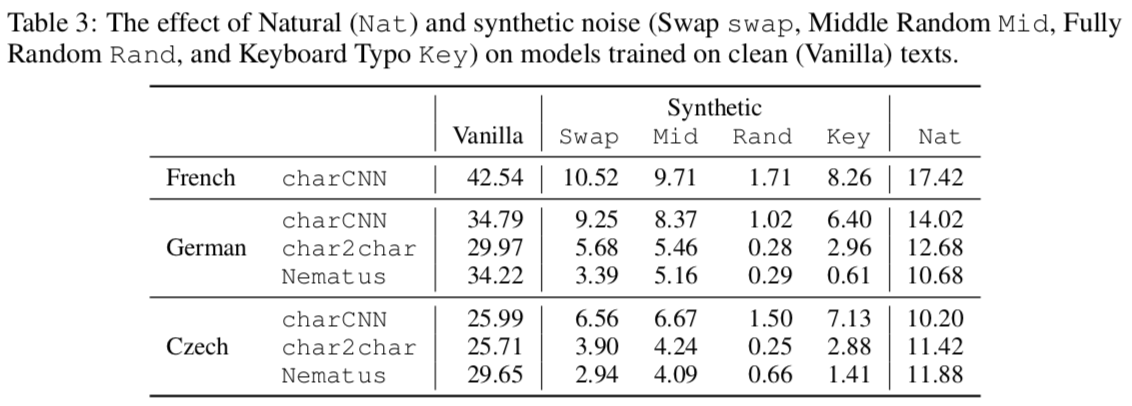

This paper endeavors to show the brittleness of neural machine translation systems. When typos or shuffling exist within words, performance plummets.

The authors are focused on models with character-level information. Particularly, the authors use three MT systems:

char2char: A fully character-level sequence-to-sequence model with attention. (Lee et al. 2017) in TACL- The Nematus toolkit my beloved, the University of Edinburgh. It’s another sequence-to-sequence model that uses byte-pair encoding, a technique for recognizing common character sequences.

charCNN: A sequence-to-sequence model whose word embeddings come from a character-level CNN.

They test on a prepared parallel corpus of TED talks for translating from French, German, and Czech to English. French conjugates its verbs. German additionally declines its nouns. Czech does both and has a notoriously complex inflection system. For each language, they extract natural noise from errors in some other corpus—for instance, single-word corrections in French Wikipedia. Any time an error exists for a word, they replace that word in the test set’s translation source text with one of its mistaken variants.

Additionally, they introduce four types of synthetic noise:

Swap: swapping two inner letters of any wordMid: shuffling all letters but the first and last. This was inspired by a popular meme from 2003.Rand: completely shuffle the letters within each wordKey: Replace one letter in each word with an adjacent key.

All systems plummetted, so the authors decided to introduce representations that were invariant toward the ordering of the letters. They did this by representing each word as the average of the embeddings (read: vector representations) of each character. This will inherently lower the highest possible BLEU score, because you’re training on a representation that loses information. Still, the degradation due to shuffling noise will be zero.

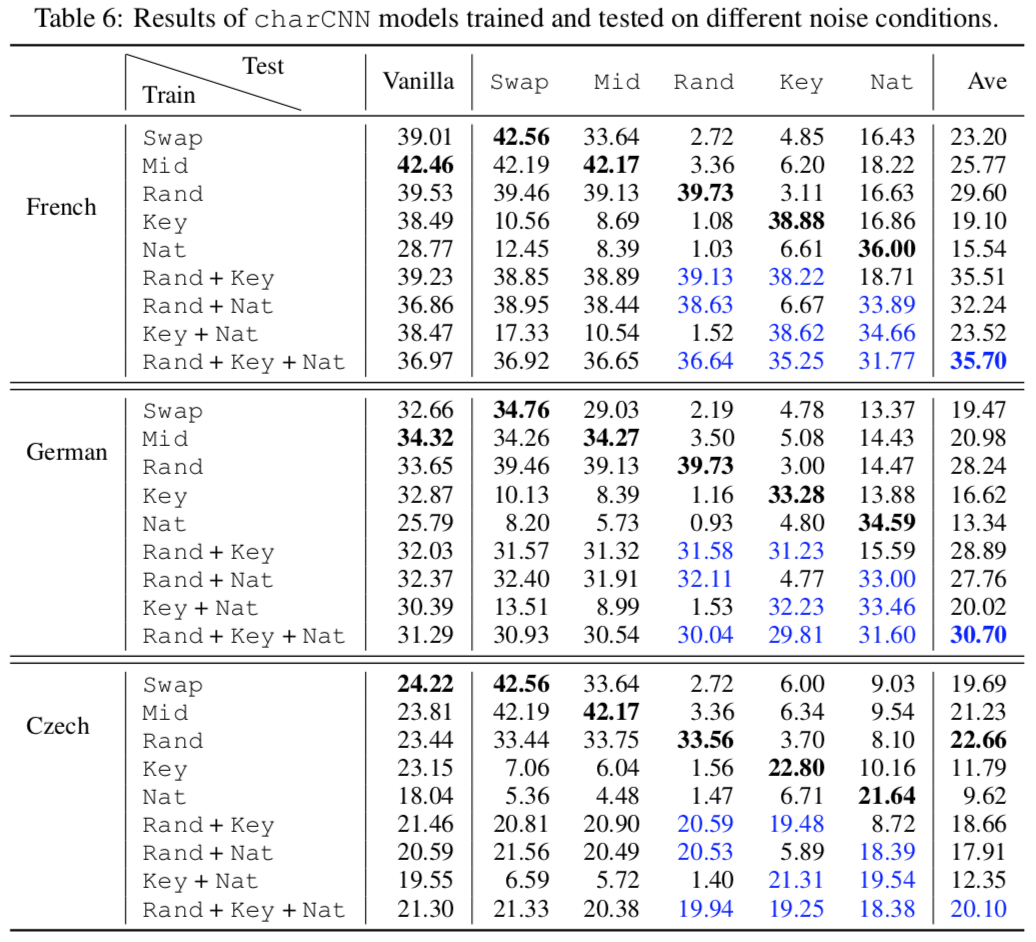

To improve performance farther, the authors generated “adversarial” training data, feeding noisy source texts as training data. When the charCNN model received noisy training data, it could handle the same type of noise well at test time, at only a small performance cost on “vanilla”, noiseless text. Finally, when training a model on all types of possible noise, it gets the best average performance—though it doesn’t excel at recovering from any particular kind of noise. The reviewers note that Google could implement this quickly. Would they, though? It jeopardizes performance on good inputs.

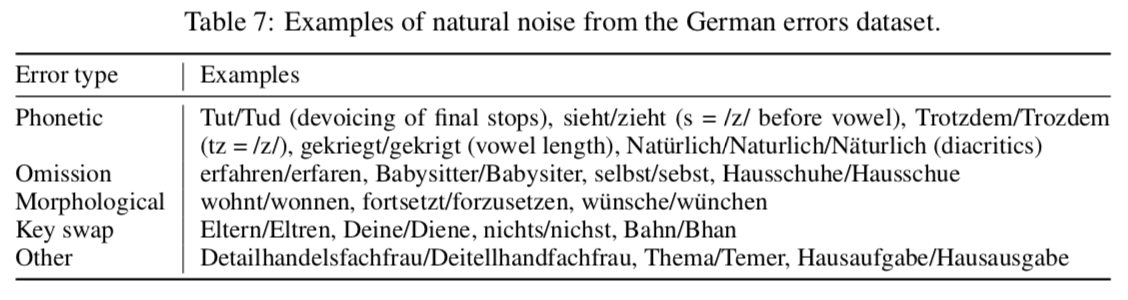

Another important observation that they make is that natural noise and synthetic noise take a very different character. Without belaboring the details, they tabulated examples of errors seen in their German corpus.

The bottom line:

- Character-based NMT models are brittle toward noisy inputs.

- Training on natural types of noise (“adversarial training”) makes it possible to recover, while losing some overall performance.

- Training on synthetic noise doesn’t help performance on natural noise.