DopeLearning: A Computational Approach to Rap Lyrics Generation

(Malmi et al., 2016) at KDD

The authors devise a method for ranking candidate rap lines conditioned on the previous lyrics. They report a 21% increase over human rappers in terms of rhyme density. Their method can be applied to other text synthesis problems such as customer service chatbots.

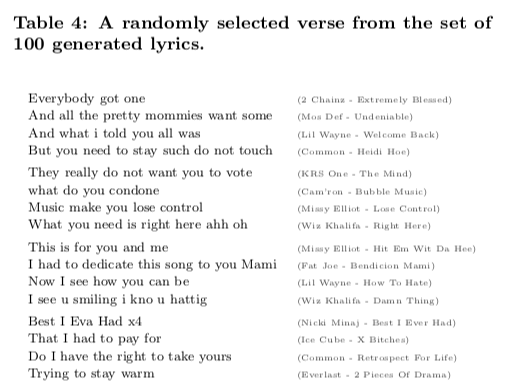

Rap music is a form of modern poetry. The authors want to generate its complex rhyme and syntax computationally, taking an information-retrieval (IR) approach. From a large database of possible lyrics, they choose the best successor for the one just heard. This lets them mix the styles of multiple artists, treating them as found art which takes a new meaning in a new context. It makes use of multisyllabic rhyme, as well as assonance rhyme: rhymes of vowels despite different consonant sounds.

Rhyme density:

- Run the lyrics transcript through g2p (grapheme-to-phoneme) to get a phonetic version. Remove non-vowels.

- For each word:

- Find the longest matching vowel sequence near the word. (This is a multisyllabic assonance rhyme.)

- Compute the density by averaging the lengths of the longest matching sequence over all words.

The rhyme density measure is suspect to me. Human rappers employ slantier rhymes. The authors note Eminem as a prime example, and this doesn’t capture his ability to rhyme “four-inch orange door hinge in storage with George”. Still, it stands up somewhat to human validation: a rap artist’s self-assessment of his rhymes aligned with the density measure in a statistically significant way.

Now that our feature function is defined, we can move to the problem definition for next-line prediction.

Consider the lyrics of a rap song S, which is a sequence of n lines (s1,…,sn). Assume that the first m lines of S, denoted by B = (s1,…,sm), are known and are considered as “the query.” Consider also that we are given a set of k candidate next lines C = {l1,…,lk}, and the promise that sm+1 ∈ C. The goal is to identify sm+1 in the candidate set C, i.e., pick a line li ∈ C such that li = sm+1.

To solve this problem, they create a model for scoring the candidates C based on the query B. The features used to determine these scores are:

- Rhyming

- End rhyme: the number of matching vowel phonemes between a candidate and the last line of B.

- End rhyme with second-to-last line of B, to get ABAB rhyme structure

- Average of match lengths for

- Structural similarity

- Similarity of line length

- Semantic similarity

- Bag-of-words similarity between the last line and the candidate

- Same, but the last k=5 lines of the query instead of just one line

- latent semantic analysis similarity

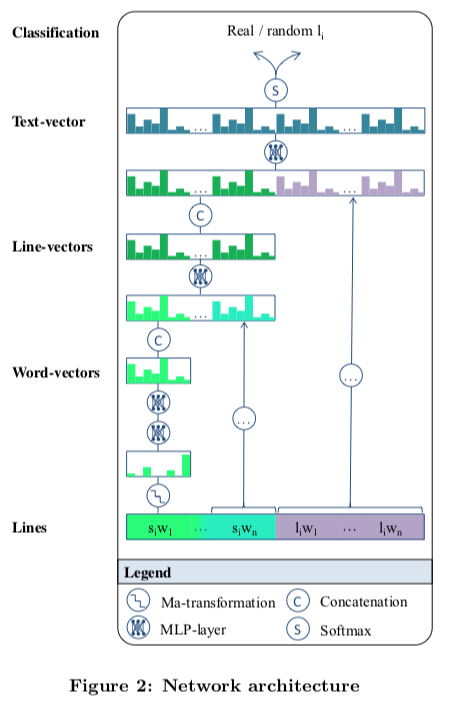

Because one of their models is a neural architecture for ranking, they need fixed-length inputs. They remove long words, and they pad short lines. They then use what sounds like a rudimentary count-based character embedding and concatenate those to get word representations.

The word vectors get appended, and we keep connecting and connecting until a softmax layer predicts whether this line follows or not. The positive examples were (naturally) attested sentences with their predecessors. Negative examples were made by taking random, uniformly chosen sentences. There were the same number of positive and negative examples. The network is trained in the normal way, backpropagating through to update weights (parameters) to maximize the likelihood of the yes/no predictions for each (history, candidate) combination.

The authors picked up a good habit: they examined examples their model got wrong. Most of the random sample of misclassified assignments was when the true lyrics’ topic changed, so the model predicted that there was a bad fit given previous lines. This isn’t unreasonable. It just shows that the model isn’t really learning high-level discourse.

The features they compute are used to train an SVM. An SVM is a linear model which seeks to separate the positive and negative examples (which are points in a vector space) by a hyperplane. The ranking aspect comes from taking a set of examples and choosing the “most positive” one, in terms of the relevance. The relevance is a linear function of the query and candidate.

Their evaluation task is predicting the correct line from a candidate list of that line and 299 other, random lines. They measure mean rank, mean reciprocal rank, and an interesting twist on recall: is the sentence in the top N ranked sentences?

Having evaluated, they now want to generate new songs. They present an algorithm which I paraphrase:

Input:

- l0: seed line

- n: lyrics length

Output:

- L: lyrics (l1, l2, …, ln)

L = [l1]

for i in range(1, n):

C <- candidates(L[i - 1])

C_ok <- filter(C, uniqueness_criterion)

L.append(argmax(C_ok, key=relevance(c, L)))

return L

Here, the key argument lets you perform an argmax. The uniqueness criterion is that a candidate c is not from the same song as the last line in L, and their last words are not identical. (Some real-world rap violates this rule, sadly.)

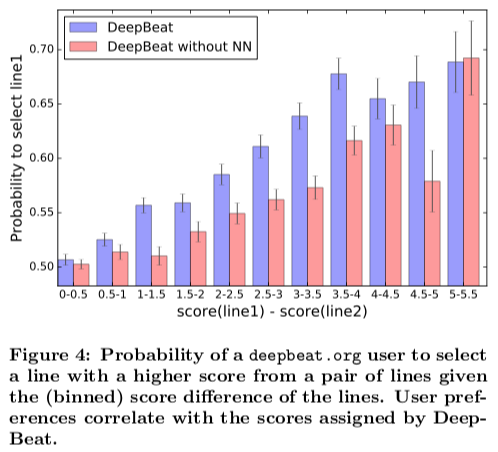

Most interestingly, they performed human evaluations. They found that the ranks they computed aligned with users’ preferences for certain lyrics, when humans were asked to choose from a list of candidates. The bigger the margin between two lines’ scores, the more likely the user was to choose the higher-scored sentence.

Good habits:

- Inspect your errors. See why you mis-classified.

The bottom line:

- Generation can be treated as a retrieval problem rather than an actual generation problem, when the vocabulary is reasonably finite.

- End rhyme is useful in predicting rap lyrics.

- Support vector machines (SVMs) can perform simple linear ranking.